by Brian A. Wilkins

brianwilkins.org

December 8, 2016

OCETI SAKOWIN CAMP, NORTH DAKOTA — Upon arriving at the camp around 6 a.m. on a dark Sunday, December 4 morning, chants of “Mni Wiconi” came from tipis far off in the distance. We walked over to what was the beginning of a water ceremony. The man on the microphone reminded photographers not to film anyone’s face without permission. People were very respectful of this request for the most part throughout all meetings and other sessions at the camp.

The final step in the water ceremony was walking to the Cannonball River, the geographic border between Oceti Sakowin and Rosebud camps. Men formed a human guard rail system for women as everyone crossed an icy, uneven walkway to get close to the frozen river. The sun, as if in synergy with the water protectors, finally peaked through the clouds around 9:27 a.m. It would be the first of several times where the power of prayer appeared to result in something positive.

Getting to know the area

The first navigation through the Oceti Sakowin Camp was facilitated by my good friend Lindsey Tarr, of the Oglala Nation. Most Oglala Sioux reside in Pine Ridge, South Dakota.

Lindsey had originally been charged by Morton County authorities with several crimes as a result of taking part in prayer activities weeks prior. She left Standing Rock after being there for a month, and came back this week to face the charges, one of which was a felony (more on this later).

After the water ceremony, we walked over to a large white dome tent, where an orientation meeting for the camp was being held. Solar-powered heating devices kept the tent warm as temperatures hovered around 20 degrees outside. Camp leaders addressed many topics during the hour-long meeting, particularly the increase in traffic around the camp due to many first-timers arriving throughout the past week. There were problems with city dwellers bringing that mentality to a camp that does not have marked streets or paved roads. “There’s no need to drive from place-to-place in the camp; just walk,” one of the women said.

Everyone was reminded that there are people who live on the camp year-round, and that we are guests who should respect their space. The community works so well because everyone embraces a helpful attitude towards each other. We were then told about other meetings that would take place later on that day.

Food available throughout camp

After leaving the morning meeting, we walked to California Kitchen, also known as “Grandma’s Kitchen.”

Not only was it nice and warm inside, but there were eggs, fruit, sausage, bacon and coffee being served to all who came through. Like most of the camp, supplies were provided through donations from people all over the world. Grandma’s Kitchen was one of several places Oceti Sakowin water protectors could eat throughout the day. We brought our own supplies so refrained from eating that time to save resources for those who actually needed them.

Porta potties seem to be within close distance no matter where we were on the camp. Internet and phone reception were spotty. But in one area, known as “Facebook Hill,” internet and phone reception was strongest.

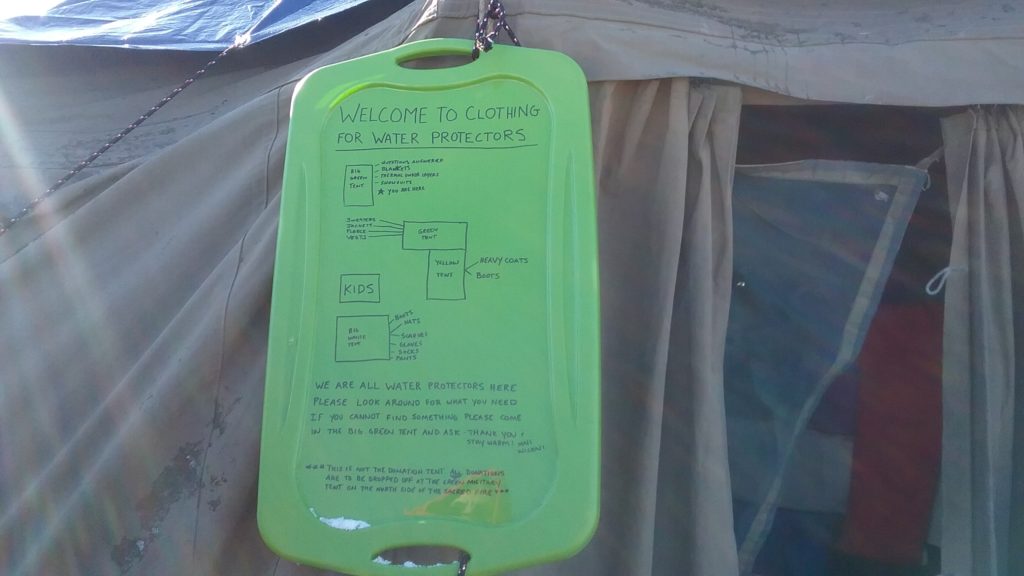

Coats, counseling and medical

There are many people across the globe who want to come to Standing Rock in solidarity with the Sioux Nation, but cannot because of other obligations and logistics. The best way to help from a far is to send donations, particularly winter weather gear, food and money for propane. NOTE: The OcetiSakowinCamp.org page is now defunct. But you can still help here.

Oceti Sakowin has received so many donations that volunteers who process all the incoming supplies are several days behind trying to sort through everything.

We visited the legal tent later in the day. That is where Lindsey discovered that the charges she faced would not be prosecuted and she did not have to attend the Morton County Courthouse in Mandan the following day. We learned more about the legal tent during a direct action training that prepares those who planned to be on the “frontline” during inevitable encounters with police.

Water protectors were reminded that all direct actions are done in a peaceful manner and based on prayer. They are instructed to do absolutely nothing that police could interpret as aggression and trigger punitive punishments by cops. Water protectors were also drilled on knowing their rights: always ask police “am I being detained” and the only information you have to give them if you are under arrest is your name, address and phone number. The idea of this training is to prepare water protectors for realities. That also meant speaking about being strip-searched by police and the trauma that is sure to follow.

The same direct action training featured one of the camp’s medics. She described to attendees how to properly rinse your eyes of pepper spray and other chemical weapons. She also emphasized the concept of “radical consent,” which is when you ask someone who appears hurt on the frontline if you can help them. Symptoms of hypothermia were discussed in detail, in light of the incident on November 20 when police sprayed water protectors with water cannons in freezing temperatures.

Veterans arrive

Thousands of veterans converged on the camp throughout the day. We went over to the Vets Check-In Tent to lend a hand where necessary. One vet showed up with a truck full of various supplies. Several nearby vets and water protectors formed a human conveyor belt and unloaded an entire truck and moved its contents to a storage tent within minutes. This was yet another example of cooperation that made the camp such a unique place.

Monday turn of events

Several interesting things happened the following day at Oceti Sakowin. Sunday was a warm, nice day for December standards in North Dakota: 27 degrees and sunny. Monday brought much colder temperatures and a blizzard that shut down most of Bismarck and all nearby roads.

Many reporters and others drove down from Bismarck just for the day to cover the happenings at the camp. Despite whiteout conditions, a bus tried exiting the camp via the only semi-smooth way out: a steep, bumpy, short incline. The bus lost control and got stuck blocking the exit out of Oceti Sakowin. Everyone was preparing to spend the night huddled in the dome. Meteorologists predicted a sustained, strong storm for the next 24 hours. But prayer and collective souls once again appeared to play a role. Snowfall suddenly stopped and a beautiful sunset resulted.

Road conditions were not pleasant. But after the bus blocking the exit was finally moved, many people used the window of opportunity to get out of the camp and back to their motel rooms in Bismarck. The snow didn’t stop for a very long; it was maybe two hours max. Heavy traffic, awful road conditions, and near-zero visibility turned a normally one hour drive from Oceti Sakowin to Bismarck, into a 150-minute adventure.

Racism In Bismarck, elsewhere in North Dakota?

During one of the meetings, a Navajo man from Arizona shared his experience while traveling to Standing Rock. He’d been told to leave a gas station near the North and South Dakota borders because the business did not want to serve Indians. Some veterans we met in Bismarck said a Native American family was denied a room at a local hotel because they were brown. The vets offered their room to the family and navigated the slick, snowy roads of Bismarck to find another room for themselves. My personal experiences with Bismarck residents yielded much different results.

My camper got stuck on a snowy road as we were leaving one hotel to check into another. We borrowed a shovel from a nearby convenience store. After an hour of trying to dig ourselves out and free the camper, an older white gentleman got out of his car and offered to pull the camper out of the ice. He tied a rope to the back of his four-wheel drive vehicle and the other end to the back of my camper. We were freed within minutes. The man then offered to lead us all the way to our next motel via the cleanest, best-plowed streets in town.

Bismarck and the rest of North Dakota are similar to all U.S. jurisdictions; there are good people and bad people everywhere.

Final thoughts

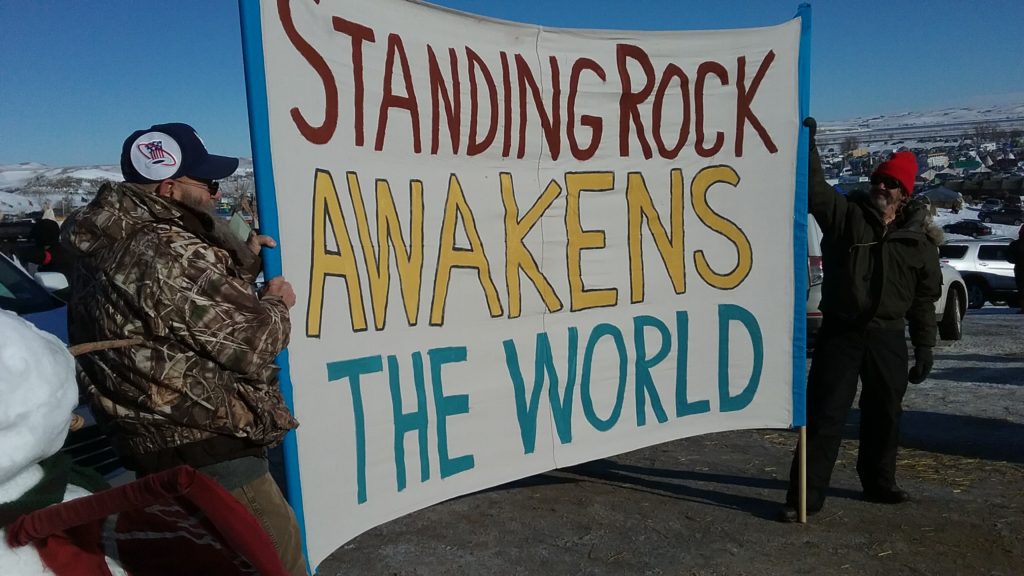

Oceti Sakowin Camp at Standing Rock is an example of great cooperation among people to achieve a common goal. The Sioux are hosting a space that not only houses permanent residents, but accommodates out-of-town individuals who chose to make the journey north in solidarity.

Its unclear if the camp will maintain its numbers after tribal leaders issued conflicting messages about the camp’s future. Regardless, Standing Rock puts on display the resiliency, strength and power the Sioux Nation and Native Americans continue to exude despite centuries of murder and manipulation at the hand of European imperialists.

For now, construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline through Sioux lands has been halted. But history has shown that the struggle is far from over.